Coronavirus is back in large numbers across Europe. Since governments began to lift lockdowns at the start of the European summer, positive cases of COVID-19 have been steadily increasing in countries that previously had the spread of the disease under control, including Spain, France, Italy and Germany.

In recent days, France has recorded its highest daily tally of the new cases since the height of the pandemic in April, while Spain faces the continent’s most significant resurgence in infections.

In the UK, certain areas have been placed into local lockdowns to stem the spread of the virus, as schools begin to reopen across its four countries, though the government says rates remain flat outside the locked down hotspots.

Most epidemiologists are reluctant to call this rise in cases a “second wave”, arguing that it is too early to say what is happening. It appears that at least some of the rise is concentrated among younger people and asymptomatic cases, and we don’t yet know why death rates are not climbing at the same rates as positive diagnoses. Countries are not yet seeing hospitals or healthcare facilities overwhelmed, as they were at the start of the pandemic.

So how worried should Europeans be about this resurgence in infections? The Conversation asked experts in Spain, France and the UK what these numbers mean, and how health authorities should respond.

France

Dominique Costagliola, Epidemiologist and Biostatistician, Inserm

In France, since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, 253,587 positive cases have been confirmed at the time of writing, causing the deaths of 30,544 people. At the end of February, the situation became epidemic, leading the government to decree general lockdown on March 17. This sweeping measure broke the chains of transmission, limiting the virus’s flow and “reset” the epidemic.

With the summer, positive cases have increased again: since mid-July, we have observed an increase in daily confirmed positive cases – 5,429 new cases were detected between August 25 and 26.

It doesn’t make much sense to compare these numbers with the numbers from March, because the situation is very different when it comes to testing. At the time, only patients with severe symptoms were screened, which is no longer the case. In spring, the number of actual cases was therefore much higher than those recorded. Especially since recent work showed that in May, only one in ten symptomatic cases was detected in France, due to a screening program that was too limited and too slow.

Though the situation has improved today, it is still difficult to know how much the epidemic is being underestimated. But one thing is certain: the number of cases is increasing more than the number of tests.

In France, since July 20, anyone aged 11 and over must wear a general public mask in closed public places, including in schools. The main problem is that this obligation mainly concerns places open to the public. Wearing a mask should be compulsory in all enclosed spaces, whatever they are, as long as they cannot be ventilated.

It should also be taken into account that the virus is spread by aerosol, in addition to large water droplets. The measurements will therefore differ depending on whether premises are air-conditioned or not, and if so, whether this is by recirculating air or by external air intake. Outside, the risk is probably lower, but preventive measures can still help to limit the spread of the virus, in particular by minimising how much we are touching our masks – for example, putting one on to enter a store, then removing it – which can also be a source of potential contamination.

One thing is certain: herd immunity, which would slow the circulation of the virus, will be very difficult to achieve. In a population where the virus circulates equally, it takes 60 to 70% of people to be infected and develop neutralising antibodies to reach herd immunity. Certainly, if the circulation is less homogeneous, as in the case of the coronavirus, which seems to circulate at “low noise” until a super-spreader event occurs, this rate may be lower.

It would be dangerous to let the virus circulate in certain groups, such as young people, in the hope of achieving herd immunity more quickly. Populations are not separated from one another: if the epidemic spreads in one group, others will be gradually affected, whether we like it or not.

This can be seen in what happened in Florida. For two to three weeks we saw the diagnosed cases increase, but mainly among young people. Hospitalisations and intensive care patients did not initially increase – these indicators do not start to move until three to six weeks later. If France also waits to take action, it will be too late, and we risk losing control of the epidemic.

While waiting for a real treatment or a vaccine, the only way to avoid a runaway epidemic is therefore to manage the circulation of the virus at an acceptable level, using widespread, rapid screening and monitoring of contacts, as well as respect for social distancing measures. This balance is not easy to maintain, but it is our only option for the months to come.

Spain

Ignacio López-Goñi, Professor of Microbiology, University of Navarra

In the worst moments of the pandemic – between the end of March and the beginning of April – more than 900 deaths per day were registered from COVID-19 in Spain.

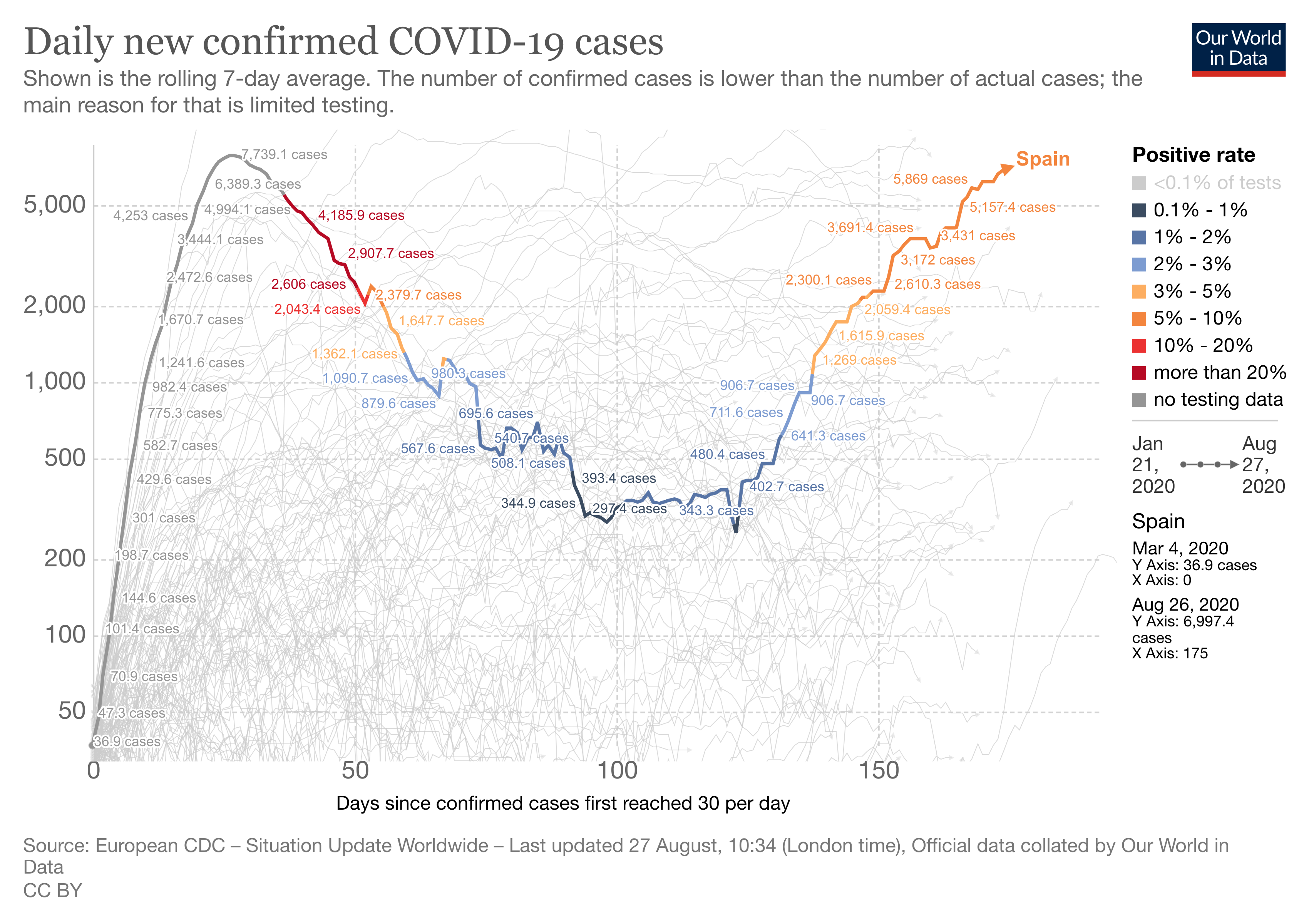

Strict confinement measures reduced the number of cases (defined as a positive result in a PCR test) to a minimum of a few hundred daily in mid-June. However, in recent weeks, Spain has reported a significant increase in the number of daily cases.

Assessing the situation is complex if we consider the difficulty of monitoring the data. For starters, there is no consensus on COVID-19 case definition between countries. In addition, there are incomprehensible data discrepancies between Spain’s autonomous communities and the federal ministry. It is thus proving very difficult to find updated data on the number of hospitalised cases and deaths, which are the most important figures we need to interpret the situation.

It is not possible to compare the situation in April with that of today. Back then, Spain performed few PCRs, which were intended only to confirm the diagnosis in symptomatic, hospitalised and severe cases. For this reason, only the tip of the iceberg was detected. Now, however, detection protocols have been tightened and all close contacts of each new positive case are subjected to testing, regardless of whether or not they develop symptoms. Since thousands of PCRs are being done, we can now detect the submerged part of the iceberg.

The detection of isolated outbreaks from asymptomatic cases at this time does not seem alarming. In fact, it is something that could be expected considering that we have been confined for three months and that only a small percentage of the Spanish population came into contact with the virus during that time. But although the situation is not alarming, the trend can be described as very worrying, given the fact that new outbreaks are detected every week.

On one hand, it is reassuring to think that, at the moment, the virus appears to be relatively stable and is not accumulating mutations that affect its virulence – more deadly second waves in some influenza pandemics were associated with genetic changes in the virus.

But what is disturbing is that we are facing a new virus for which, in principle, the population does not present immunity. That could favour the appearance of a new wave. What we cannot rule out is that some of the outbreaks that are detected now end up getting out of control and causing bigger problems. Hence, the importance of strengthening control.

On the part of individuals, this is about preventing contagion at all costs with masks, social distancing and good hygiene, in addition to trying to avoid crowded, indoor spaces where many people are close together for a long time.

As for the health authorities, they have no choice but to take the lead. The virus does not care if we call this an outbreak, a flare-up or a second wave. The virus does not recognise our internal or external borders. We need coordination, tracking, quarantine and isolation, and the strengthening of our primary care system. And we must by all means necessary avoid the virus reaching our hospitals again.

Regardless of whether there is a second wave, adding SARS-CoV-2 to the list of viruses and bacteria that cause respiratory infections during the winter could be a very serious problem. Since no vaccine will be available this winter, we must prepare for the worst.

UK

Jasmina Panovska-Griffiths, Senior Research Fellow and Lecturer in Mathematical Modelling, UCL; Lecturer in Applied Mathematics at The Queen’s College, Oxford University

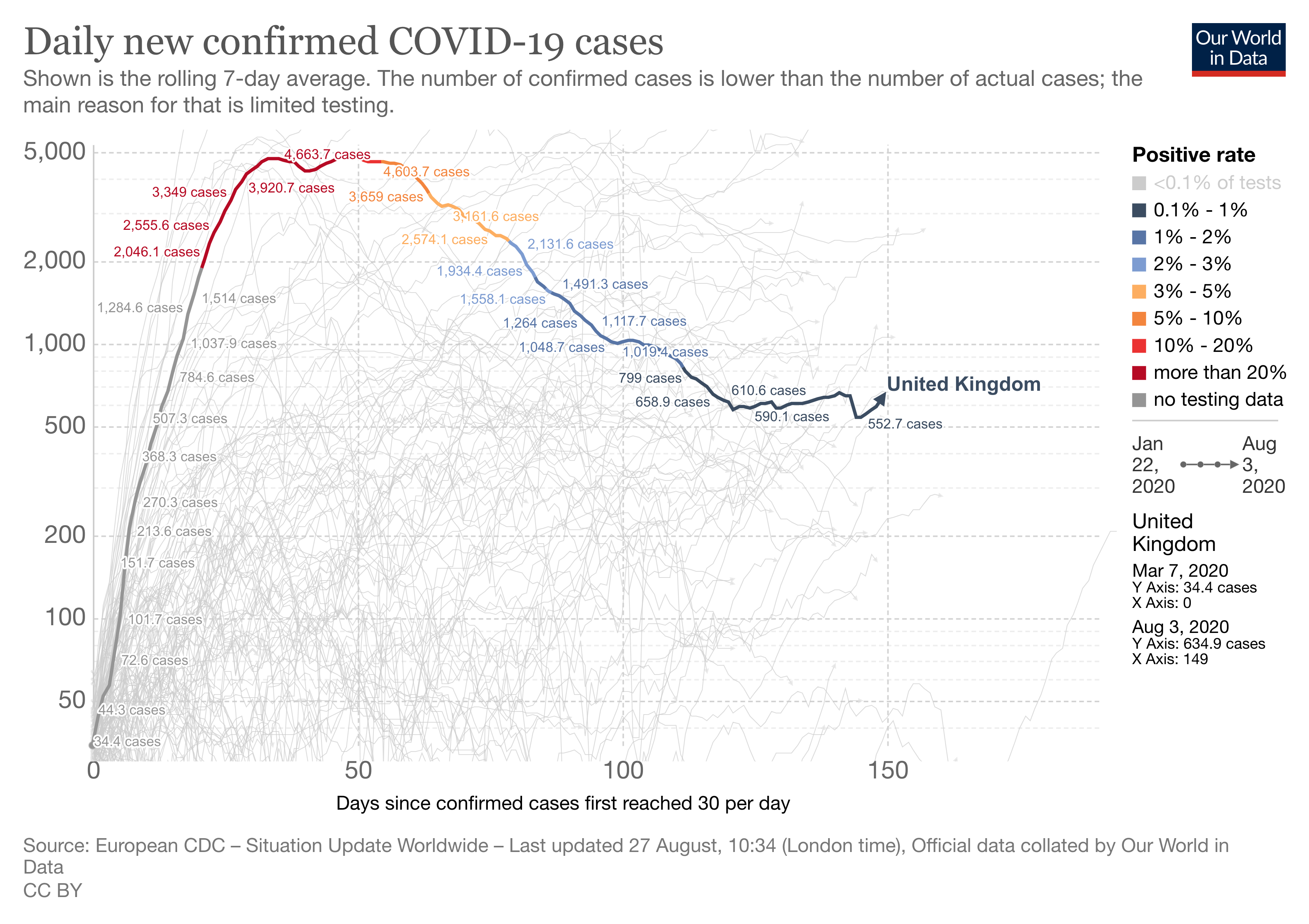

In the UK, 327,798 people had tested positive for coronavirus and there had been 41,449 deaths associated with COVID-19 as of August 26. It has been reported that England has had the longest period of excess mortality of any country during the pandemic. While the disease struck earlier in continental Europe, it has hit the UK very hard ever since it arrived. Still, the UK is not currently seeing a rise in cases to the extent of France and Spain.

As a result of the lockdown and reduced number of the physical contacts which drive infections, the number of new COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations and deaths started to decline after peaking in April, reducing the R number, which indicates how many people someone with the disease will go on to infect, to below one. As a consequence, phased release of lockdown measures started with partial reopening of society from June. However, daily confirmed numbers started to creep up again in July. Current estimates suggest that it is uncertain that the national R is actually below one, the threshold for keeping the epidemic in check, with regional and local variations.

With these recently reported rises in the daily number of cases and localised outbreaks, further easing of the lockdown measures in England was postponed on July 31. Instead, the government made the use of face coverings mandatory in more public places.

Rising case numbers could mean three different things. First, it is possible that this is a second wave of COVID-19. Second, it could mean that the disease is spreading in clusters as localised outbreaks.

Or, third, the rising numbers may show that relaxing lockdown restrictions has ended the suppression of what the WHO has called one big COVID-19 wave that will oscillate over time.

It’s currently too early to say which of these scenarios the UK is facing.

A second wave in the UK would imply a large surge in the epidemic metrics, such as the number of new infections, hospitalisations or deaths associated with coronavirus. It is worth keeping in mind that additional waves have characterised all of the last four pandemics – the 1918 Spanish flu, the 1957-8 Asian flu, the 1967-8 Hong Kong flu and the 2009 swine flu – so this is very much a possibility.

Notably, although we have seen a rise in the number of new cases in the UK, the number of deaths and hospitalisations associated with COVID-19 has not increased. This may be because the recent increase in the number of new cases is partly being seen in younger people, which is different to the onset of the epidemic when the biggest COVID-19 burden was in elderly people, who are at greatest risk of hospitalisation and of dying from the disease. The UK has also increased its testing capacity since the onset of the epidemic, which is bound to bring up the number of confirmed cases.

These questions are made more urgent by the fact that schools have reopened in Scotland, and will reopen in England, Wales and Northern Ireland on September 1. This is the first real step towards a wider reopening of society, which will allow parents to go back to work and for wider mixing among the community.

My recent modelling work suggests that we can avoid a second wave associated with reopening schools, alongside reopening society, if enough people with symptomatic infection can be tested and their contacts traced and effectively isolated. An effective test-trace-isolate strategy could also work if, instead of facing a large second wave, we are faced with smaller local outbreaks come September.

Whatever the rising number of cases means, the ability to test more people as soon as symptoms appear, effectively trace their contracts, and isolate those who have been diagnosed or show symptoms is imperative for future control of COVID-19 in the UK while we await an effective vaccine.

Dominique Costagliola, Épidémiologiste et biostatisticienne, directrice adjointe de l'Institut Pierre Louis d’Épidémiologie et de Santé Publique (Sorbonne Université/Inserm), directrice de recherches, Inserm; Ignacio López-Goñi, Catedrático de Microbiología, Universidad de Navarra, and Jasmina Panovska-Griffiths, Senior Research Fellow and Lecturer in Mathematical Modelling, UCL

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()